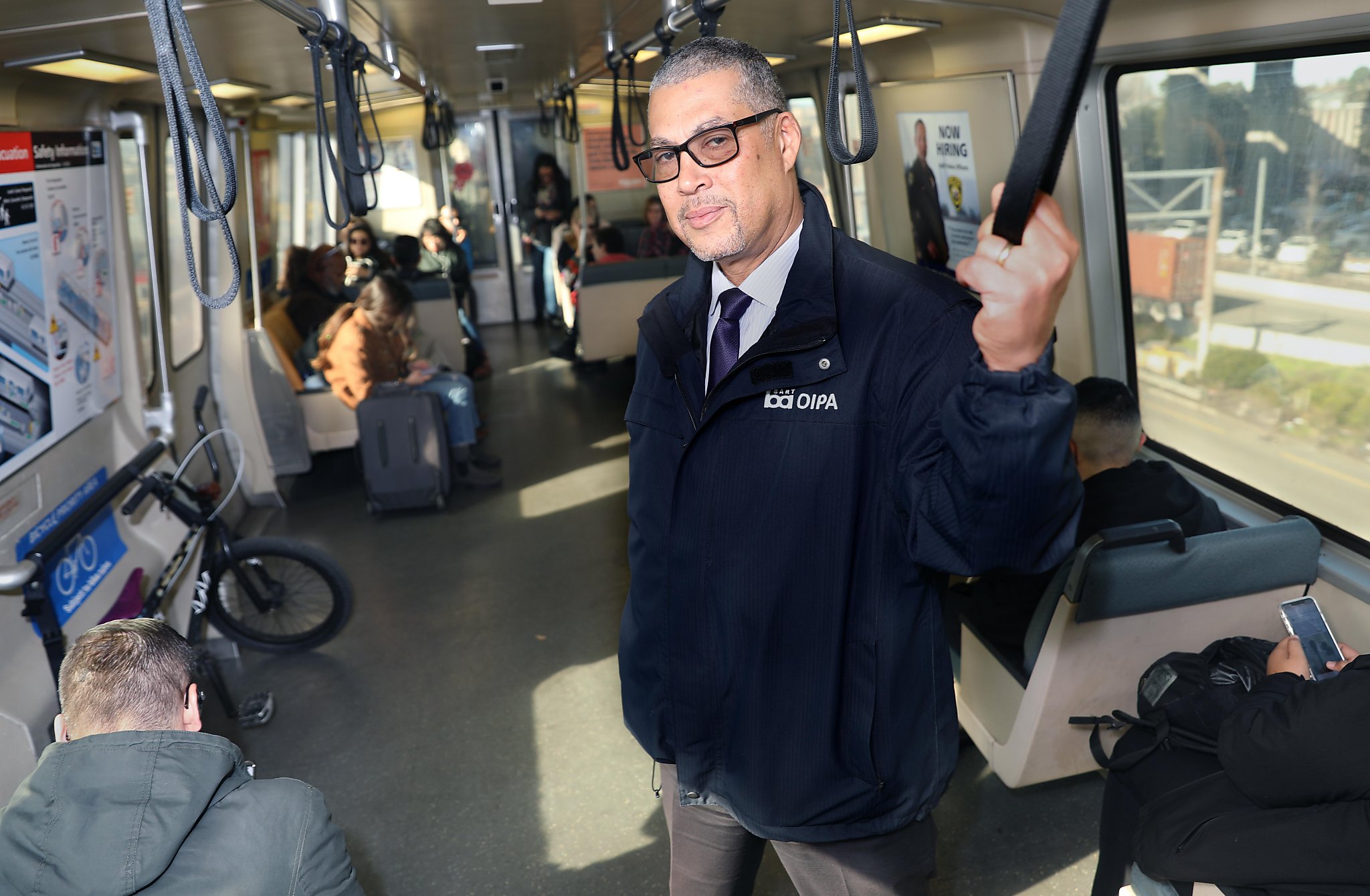

BART’s independent police watchdog launched an unofficial listening tour Monday morning, ambling along the platform at 19th Street station before riding the train to West Oakland.

Some commuters stopped to shake his hand but many breezed by, unfamiliar with the tall man in a navy blue windbreaker who aims to keep BART police fair and just.

Though he remains largely out of sight and tries to steer clear of political battles, Russell Bloom plays a key role in a transit agency that’s struggling to balance enforcement with civil liberties. In the past year alone, BART has grappled with high-profile violent crimes, open-air drug use, a surge of homeless people on trains and an emotional debate over whether to ban panhandling.

It’s also taken a harder line on fare cheats, reflected in the uptick of fare evasion-related complaints that come to Bloom’s office.

He and other officials acknowledge the challenge of policing a rail system that spans a complex and diverse Bay Area, while building trust with 400,000 commuters who board the trains every weekday. Yet Bloom praises BART for making strides since an officer shot and killed 22-year-old Oscar Grant on the platform of Fruitvale Station 11 years ago.

“The evolution of the department really began with the hiring of (former) Police Chief Kenton Rainey,” in 2010, he said. Rainey strengthened internal affairs, required patrol officers to wear body cameras and brought the police culture in line with national trends. Subsequent chief Carlos Rojas also emphasized community relations during his two-year tenure, even as he beefed up foot patrols, hired more officers and used BART’s surveillance network to increase arrests. Rojas retired in May, and BART has not named a replacement.

“What I have seen is a department that’s committed itself to improving its practices, to being self-reflective and to creating a culture of accountability and responsibility,” Bloom said. He firmly believes that BART’s effort to connect with the communities it serves compliments its work to boost public safety.

The concept of a civilian police review board or independent auditor isn’t new, but only in recent years did it start to take off across the country. Traditionally, police departments were responsible for their own investigations, and to a large extent that’s still the case, even at BART. Most complaints go to internal affairs, unless the person filing the allegations specifically seeks out the independent auditor.

It resembles other models of customer service. “When you buy a defective product at Target, you call Target and ask to speak to a supervisor,” Bloom said. You don’t call the Bureau of Consumer Protection.

Still, serious cases, such as an officer-involved shooting, would automatically trigger a review by the independent officer. He also investigates accusations of police officers lying, as well as instances of excessive force.

Bloom took the job of independent police auditor four years ago. The son of a criminal defense attorney, he studied law at the now-defunct New College of California and went on to chair the Berkeley Police Review Commission. He became an investigator for BART in 2014, under former police auditor Mark Smith.

“This is the work that Russell was born to do,” said BART Board President Lateefah Simon, an ardent social justice advocate and the only black board director. As such, she’s often the one fielding complaints when riders feel their civil rights were violated.

“Whether it’s texts or on Twitter, the stuff comes to me,” Simon said. “And I call Russell immediately. I talk to him five or six times a week.”

The office of the independent police auditor was among several outcomes of the fatal shooting of Grant — a moment that haunts BART to this day.

Creating a two-pronged system of accountability was key for the transit agency to claw its way out of that crisis. Bloom and his two staff members work with an eleven-member police citizen review board to investigate complaints of alleged misconduct and recommend discipline when appropriate. Additionally, Bloom helps craft department policies and rules. He’s most proud of a 2015 policy that lays out guidelines for officers interacting with transgender people.

To date, the office of the independent police auditor has completed 74 investigations. Bloom receives an average of 22 complaints annually — a number that shot up to 42 last year, which Bloom attributes to greater public awareness of his office. Last year his closed eight investigations and sustained findings for six allegations: one for improper arrest or detention, one for conduct unbecoming of an officer and four for an officer’s failure to activate a body-worn camera.

Representatives of the BART Police Officers Association say that’s not enough to justify the office’s $750,000 annual budget.

“The majority of the complaints are for rudeness,” said the association’s president, Officer Keith Garcia. “He (Bloom) makes one clearance a month, and we don’t really have officers violating people’s rights. So what are the taxpayers getting?”

Grant’s uncle, Cephus Johnson, noted that the office of the independent police auditor and the citizen review board “are not as effective as they could be.” But don’t blame the officials, he said. Blame the lack of resources.

While BART police have evolved over the past decade, the department has also stumbled. A Chronicle investigation in 2018 revealed that two-thirds of the people banned from BART property are black, which raised concerns of racial profiling. Nearly half of BART’s civil citations for proof-of-payment go to African American riders, despite built-in guards to ensure that enforcement is impartial.

Any disparity points to a potential problem, Bloom said, even if BART has the best intentions.

Yet the biggest hurdle is capturing the public’s attention. A September survey showed that only 11% of riders knew the transit agency has an independent police auditor. His office still handles far fewer complaints than the 119 that go to BART police internal affairs each year.

“It’s people’s natural instinct that if they want to complain about a BART police officer, they go to the police department,” he said. “But I believe people who choose to do that likely don’t know we exist.”

Rachel Swan is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: rswan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @rachelswan

"Key" - Google News

January 07, 2020 at 07:00PM

https://ift.tt/37KEW7X

BART’s independent police watchdog: A key to reform, even if you’ve never heard of him - San Francisco Chronicle

"Key" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2YqNJZt

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

No comments:

Post a Comment